The Unspoken Contract

I used to despise top-down culture, but I can see some potential benefits, only if we do it right

The debate over top-down versus bottom-up product culture is often framed as a simple efficiency contest. Which model ships features faster? Which one innovates more?

I’ve been in both ends, and sometimes a mix in one company depending on the project. I used to dislike the idea of top-down, as it is considered as limiting. However, after talking to friends about it, it feels like they all have trade-offs. Sometimes it could also be beneficial, if and only if we adhere to one thing: who’s accountable for the outcomes.

The true, fundamental difference lies not in speed or innovation!

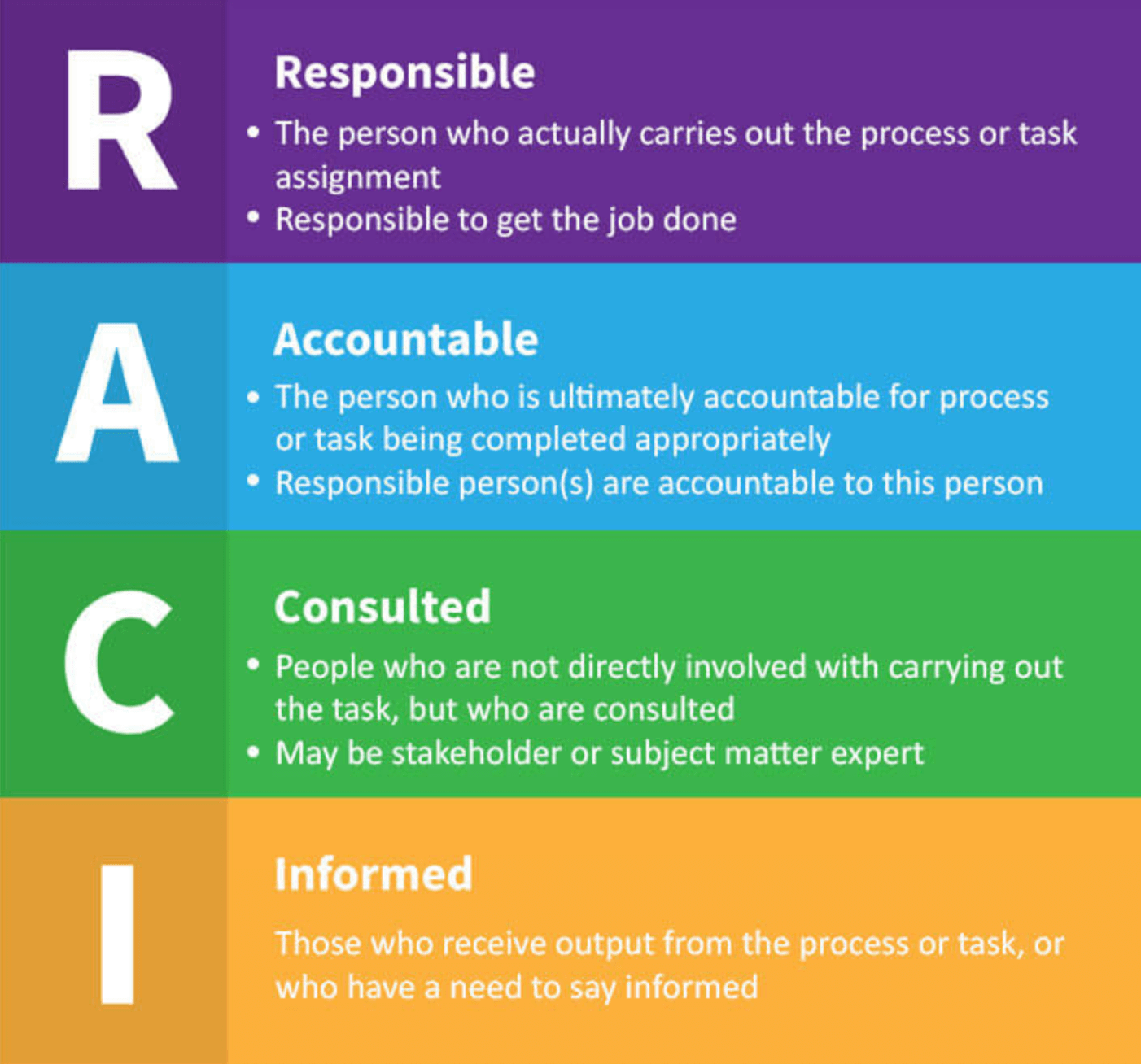

Let’s borrow the RACI framework:

This distinction is more than semantics; it is the cornerstone of fair organizational design, and it’s perfectly illuminated by two letters from the classic RACI framework: R (Responsible) and A (Accountable).

If you operate in a strict top-down culture, your teams should be considered Responsible, but never truly Accountable. In contrast, a bottom-up culture demands both.

So technically, in top-down culture, it could be easier on you if you’re not in leadership, or you’re heavy on execution. If, and only if, they’re doing it properly.

The greatest mistake and worst implication to your performance as an executor is that if you’re also held accountable for the outcomes.

If it’s a bottom-up culture, then you’re in a more difficult situation, because you’re also responsible for the outcomes. Whatever you plan and propose, you have to shepherd it along. If you fail, then you lost, or at least people will hold you super accountable.

Top-down: “let us do it, but you’re accountable”

In a top-down product organization, strategy and vision cascade from the executive suite. The mandate is clear: “Build X feature because the market demands it,” or “We must integrate Y technology to meet our competitor.”

In this scenario, the product team—the managers, designers, and engineers—becomes the highly capable execution engine.

The team’s primary role is Responsible (R). They are responsible for the execution. They must write clean code, ensure minimal bugs, meet deadlines, and deliver the feature exactly as scoped. They are responsible for the how.

However, they must be exempt from the heavy weight of Accountability (A).

Accountability, in its purest form, means being answerable for the outcome. Did the feature drive adoption? Did it increase revenue? Did it solve the customer’s problem?

If a product team is simply executing a mandate handed down from the top, they are executing someone else’s strategy. Their authority is limited to the tactical choices (how to build it), not the strategic choices (what to build and why).

To hold a team accountable for the failure of a strategy they didn’t author is fundamentally unfair. It creates a toxic environment where consequences are divorced from the power to affect change. A great execution team can’t save a flawed strategic decision. In the top-down model, the senior leader must retain the A for the strategy, while the team owns the R for the build.

Bottom-up: “let us decide, but we’re accountable”

The bottom-up product culture is an entirely different ecosystem. In this model, the organization empowers product teams with a problem space and clear goals, but gives them the full authority to define the strategy, prioritize the work, and choose the solution.

This autonomy is liberating, but it comes with a necessary and appropriate weight.

Here, the Unspoken Contract is whole. The team is both Responsible (R) and Accountable (A).

Responsible (R): They still own the execution, the delivery, the quality control—the how.

Accountable (A): Because they had the authority to define the strategic problem, to run the experiments, and to ultimately launch the solution, they must be answerable for the results—the did it work.

When a bottom-up team fails, it is a valuable learning experience because the failure is a direct function of the team’s strategic choices. They own the entire end-to-end outcome, and thus, holding them accountable is both fair and highly motivating.

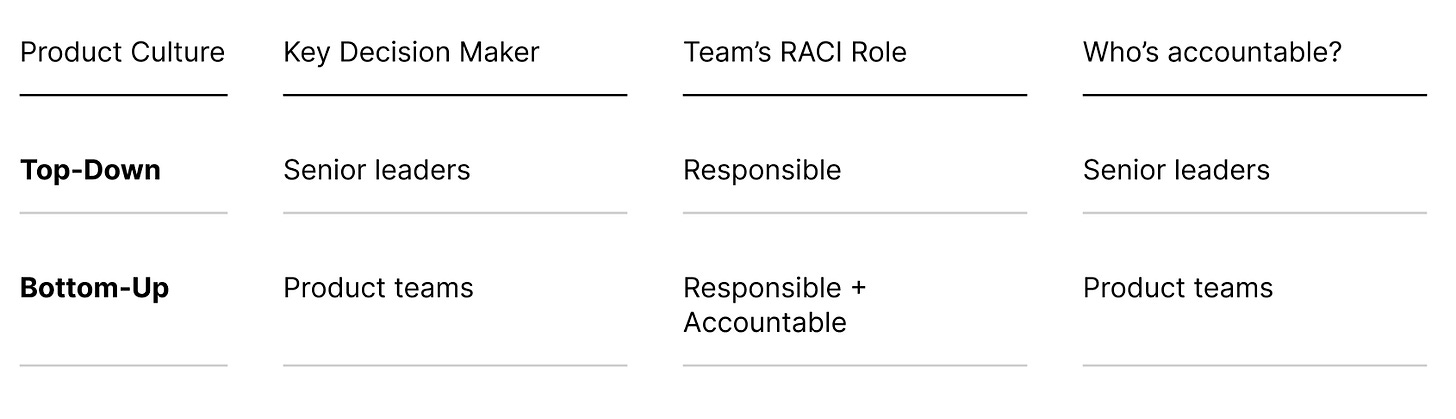

This is how it maps out, more or less:

How about the C and I portions? Consulted and Informed will still be involved in both cultures, but their roles are kind of different. Here’s how I see it:

In the top-down product environment, the flow of information is largely a one-way street, running from the highest echelons down to the execution layer.

The Consulted (C) becomes narrow and highly tactical. For example, engineering team might be part of this.

They are called upon to answer questions like: “Can we build this specific feature on time?” or “What are the technical constraints of implementing this mandate?” Their expertise is valued strictly for optimizing the means of execution, not for validating the strategic end goal. They are consulted on feasibility, not desirability or viability.

The Informed (I) teams are the recipients of the strategic mandate, the deadlines, and the executive vision. They are kept in the loop on what must be done.

For example, the Customer Service team. They will be informed on what strategies and products we’re launching, and they will have their own cascaded tasks or assignments. It is highly directive.

Whereas in the bottom-up product environment, the engineering team will become more of a strategic partner, and maybe even part of the responsible. The Customer Service team will be a collaborator, perhaps even defining in some parts of the strategy.

In conclusion

The insight derived from mapping organizational culture to RACI roles provides a critical test for any leadership team. Here’s my takeaway:

If you expect your teams to be Accountable (A) for outcomes, you must give them the authority of a bottom-up model. This means trusting them to define the problem and the solution, not just the technical specifications.

If you choose to retain that authority at the executive level (the top-down model), you must, for the health of your culture, relieve the teams of the Accountability (A) for results. Celebrate their Responsibility (R)—their effort and quality execution and accept the strategic accountability yourself.

The goal isn’t to pick a single “best” culture, but to ensure that wherever the power to make decisions resides, the consequences for those decisions follow precisely behind it. That is how trust is built, and how high-performing teams, in any culture, can thrive without succumbing to the burnout of unfair expectations.

—

Hat-tip to my friend Vikram Managoli for the discussion that inspired this article.